Underneath the Spreading Chestnut Tree

I loved you and you loved me -- but did we love each other enough to overcome our deepest failures and triumph against evil?

[This post is highlighted in a video exploration of the Crowned and Conquering Child, which you can view here.]

1984’s Chestnuts

The bleak and totalitarian future dystopia meticulously held up to the dying light of human foresight that is ‘1984’ by George Orwell is taught in nearly every school, held as a deterrent to every communist sympathizer, and analyzed by every literary noob in history. And yet I’ve never seen a single analysis of what I’m about to share with you.

When I taught the book semester after semester, I became intimately familiar with more than just the common tropes and narratives, themes and character analyses, and philosophical takes on economics, politics, and sociology. When I read something over and over, I can’t help but continue to pick apart every detail. The most obvious symbol in the entire book is the one least picked apart and analyzed, however, and that is the Chestnut Tree.

Spoiler alert: when Winston is finally broken by the Party, by his idol and confidante representing Big Brother, and by the deepest fears within his own heart and mind, we find him afterward sitting at the Chestnut Tree Cafe, a place for disgraced Party members. This is not the first time we encounter the Chestnut Tree Cafe.

Part I

The song “Under the spreading chestnut tree / I sold you and you sold me…” is introduced.

This refrain foreshadows betrayal and broken bonds, symbolizing how the Party destroys personal loyalty.

The Chestnut Tree Café is described as a place where disgraced Party members—those who have been purged or fallen out of favor—spend their time.

It is bleak, filled with telescreens, and represents conformity and defeat.

Part III

Winston sits alone in the Chestnut Tree Café, drinking gin.

He reflects on his betrayal of Julia, his lover, and the song plays again.

Winston has finally accepted the Party’s control and professed his love for Big Brother.

The song resurfaces, underscoring the theme of betrayal.

Curiosity drove me to ask whether or not there really existed, in George Orwell’s world, a song about a Chestnut Tree. It turned out there did and it was quite popular, though none in my generation or the generation preceding me had ever heard of it.

Perhaps my Grandmother danced to this popular song in Big Band or Orchestral renditions, but most of us are already so removed from our grandparents’ worlds that I couldn’t know. Very apropos of the point of this very exploration I write her today, we have not held the thread that may have informed us of such things. All my grandparents had long since died by the time I wondered, circa 2012, whether they would have known and loved this song. I have come to love it deeply, myself. Maybe you will too.

Underneath the Spreading Chestnut Tree

Glen Miller Band

Recorded in 1939 by the Glen Miller band and quickly rising to hit popularity, echoing throughout swing and orchestral dance halls, the lyrics to this song are as such:

Underneath the spreading chestnut tree

I loved him and he loved me

There I used to sit up on his knee

′Neath the spreading chestnut tree

There beneath the boughs we used to meet

All his kisses were so sweet

All the little birdies went “tweet-tweet”

‘Neath the spreading chestnut tree

I said “I love you”, and there ain′t no if’s or but’s

He said “I love you”, and the blacksmith shouted

“Chestnut!”

Underneath the spreading chestnut tree

There he said he′d marry me

Now you oughta see our family

′Neath the spreading chestnut tree

There beneath the boughs we used to meet

All his kisses were so sweet

All the little birdies went “tweet-tweet”

‘Neath the spreading chestnut tree

Underneath the spreading chestnut tree

There he said he′d marry me

Now you oughta see our family

‘Neath the spreading chestnut tree

I made my students listen to the song, choose quotes from the song that either supported or contrasted with the themes of the book, and write about why George Orwell might have used this song to change and transform so completely out of its original intent. I imagine you’ve already done something of the same.

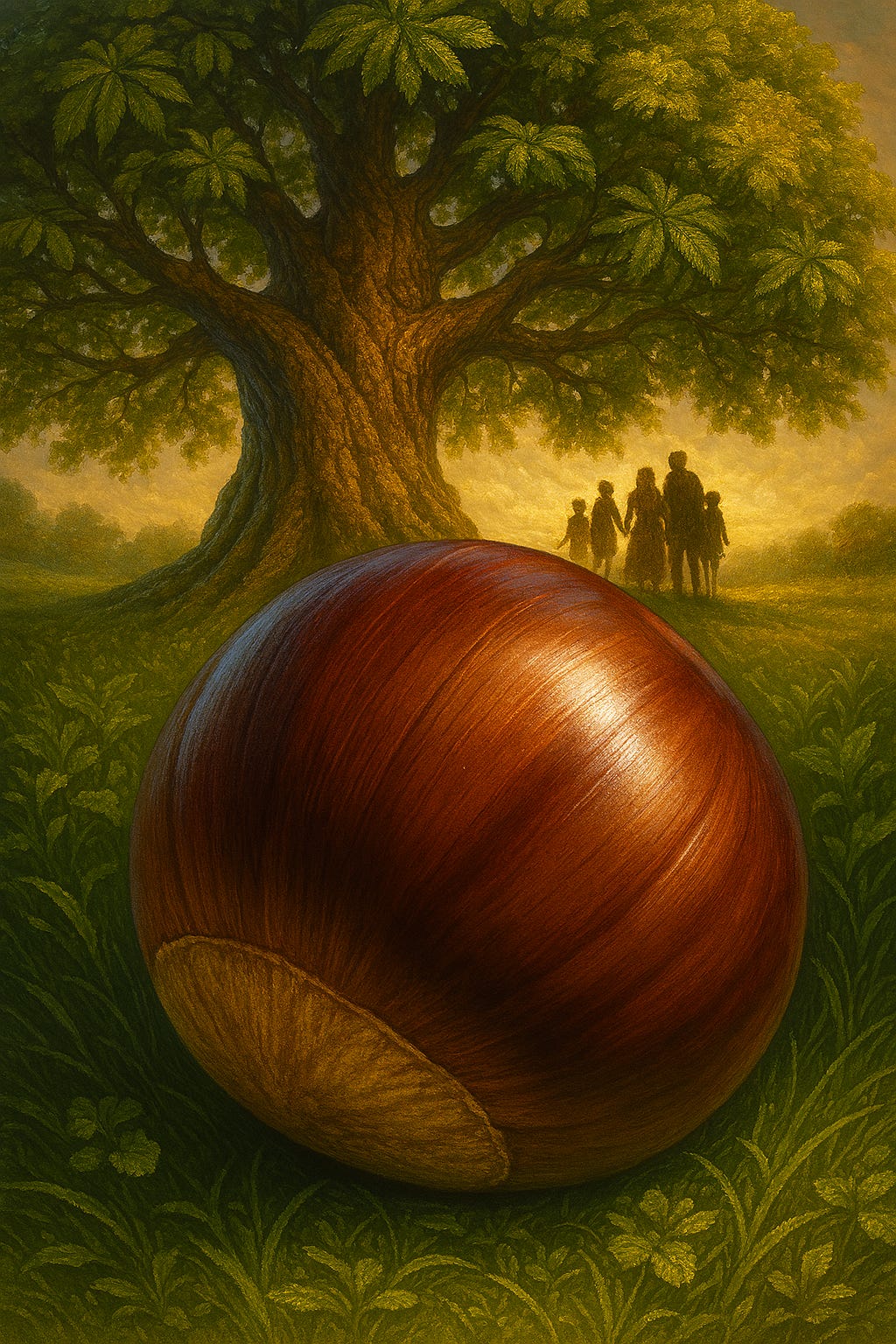

Clearly, the Chestnut Tree in the song is vital, full of promise and growth that spans forward into perpetuity. The family created via the love cemented in the song also underscores the power and goodness of simple life, of marriage and love, and of the future that is bright when we are fruitful and united.

In the book, on the other hand, Winston hates women, despises connection with them, lusts for Julia only because she is a rebel against a system he hates even more than women, and ultimately betrays her to save himself because he is a crushed, weak, disconnected and empty man. The Chestnut Tree, in the book, therefore, is the life and future that cannot be, once the Party and Big Brother have found their foothold in the minds and hearts of mankind.

The Village Blacksmith

Like me, then, you may wonder what inspired the Glen Miller band’s use of the simple chestnut tree as a symbol for the unity and prosperity of the simple bonds of family and love. Like me, then, you may also enjoy knowing the predecessor of the song’s symbolism lies in a beautiful and poignant poem by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, written in 1840, almost exactly a century prior.

Under a spreading chestnut-tree

The village smithy stands;

The smith, a mighty man is he,

With large and sinewy hands;

And the muscles of his brawny arms

Are strong as iron bands.

His hair is crisp, and black, and long;

His face is like the tan;

His brow is wet with honest sweat,

He earns whate’er he can,

And looks the whole world in the face,

For he owes not any man.

Week in, week out, from morn till night,

You can hear his bellows blow;

You can hear him swing his heavy sledge,

With measured beat and slow,

Like a sexton ringing the village bell,

When the evening sun is low.

And children coming home from school

Look in at the open door;

They love to see the flaming forge,

And hear the bellows roar,

And catch the burning sparks that fly

Like chaff from a threshing floor.

He goes on Sunday to the church,

And sits among his boys;

He hears the parson pray and preach,

He hears his daughter’s voice,

Singing in the village choir,

And it makes his heart rejoice.

It sounds to him like her mother’s voice,

Singing in Paradise!

He needs must think of her once more,

How in the grave she lies;

And with his hard, rough hand he wipes

A tear out of his eyes.

Toiling,—rejoicing,—sorrowing,

Onward through life he goes;

Each morning sees some task begin,

Each evening sees it close;

Something attempted, something done,

Has earned a night’s repose.

Thanks, thanks to thee, my worthy friend,

For the lesson thou hast taught!

Thus at the flaming forge of life

Our fortunes must be wrought;

Thus on its sounding anvil shaped

Each burning deed and thought!

The poem emphasizes the goodness inherent in working for your life, in not being a slave to any man, in recognizing your hardships as the consequences of the gifts of love and life, and in being satisfied with the simplicity of a life of creation and interconnection. There is community, but it is chosen and not forced. There is identity, but it is a byproduct of living a good life of self responsibility, not adopted as a means of gaining status or proving virtue in a false social stratification. This poem is a perfect antithesis to the dark and twisted lack of humanity presented to us in 1984, where mankind has lost everything worth living for.

From My Arm-Chair

This story gets even better when you find out that Longfellow wrote ‘The Village Blacksmith’ in part about a real Chestnut tree in Cambridge, Massachusetts. When this very real and beloved tree was eventually cut down, schoolchildren took the tree and turned parts of it into a chair. They presented this gift to Longfellow, who then wrote the poem, “From My Arm-Chair”.

Am I a king, that I should call my own

This splendid ebon throne?

Or by what reason, or what right divine,

Can I proclaim it mine?

Only, perhaps, by right divine of song

It may to me belong;

Only because the spreading chestnut tree

Of old was sung by me.

Well I remember it in all its prime,

When in the summer-time

The affluent foliage of its branches made

A cavern of cool shade.

There, by the blacksmith’s forge, beside the street,

Its blossoms white and sweet

Enticed the bees, until it seemed alive,

And murmured like a hive.

And when the winds of autumn, with a shout,

Tossed its great arms about,

The shining chestnuts, bursting from the sheath,

Dropped to the ground beneath.

And now some fragments of its branches bare,

Shaped as a stately chair,

Have by my hearthstone found a home at last,

And whisper of the past.

The Danish king could not in all his pride

Repel the ocean tide,

But, seated in this chair, I can in rhyme

Roll back the tide of Time.

I see again, as one in vision sees,

The blossoms and the bees,

And hear the children’s voices shout and call,

And the brown chestnuts fall.

I see the smithy with its fires aglow,

I hear the bellows blow,

And the shrill hammers on the anvil beat

The iron white with heat!

And thus, dear children, have ye made for me

This day a jubilee,

And to my more than three-score years and ten

Brought back my youth again.

The heart hath its own memory, like the mind,

And in it are enshrined

The precious keepsakes, into which is wrought

The giver’s loving thought.

Only your love and your remembrance could

Give life to this dead wood,

And make these branches, leafless now so long,

Blossom again in song.

Can you imagine the interconnected but self-reliant community of thoughtfulness and love that brought all these pieces together? A blacksmith set up beneath a chestnut tree in a village connected through shared culture, self respect, and mutual interdependence. The hard work, love and loss of the blacksmith intertwined with the strength of a tree with deep roots and powerful sustenance to inspire a poet to capture the themes of life and death, struggle and success, love and loss, community and identity. The poem inspired a people and culture much further out than the little town in which it was written, living on so long that school children then honored the poem decades later, when the tree died.

Our Roots are Intertwined

Turning the tree into the chair to support the old man in the twilight of his life, the poet reflects on all the stages and moments that come through a life, like the seasons and years of a tree, to ripple out into eternity the power of the simple heart of man. The ripple traveled so far that it inspired a song that caught the heart of a nation again, a century later, echoing back so fully that no one questioned why, in the song, a random blacksmith shouts, otherwise nonsensically, “Chestnut!”

Today, we hear the song and cannot see why a blacksmith would even be around to shout anything and why, for the sake of love and celebrating a marriage, you might shout the name of a random nut. We have nearly lost the thread that connected the people of nearly 100 years ago to the people of nearly 100 years before that.

In the book, 1984, Orwell emphasizes exactly this disconnection. He highlights exactly this lack of memory. He underscores the dissonant way in which even what we once held most dear cannot bring us back to our roots, once we have chopped them down. He shows us how you can understand a dark vision of a dystopic political and social evil once it is laid out before you, but unless you can understand the heart of what allows it to thrive, you will suffer the fate of Winston and everyone else at the Chestnut Tree Cafe: ultimate defeat that you nonetheless created yourself.

This is why the true message of 1984 is not to rail against communism, as every professor and teacher has said for 80 years. The ultimate intention is not to steer you away from a surveillance grid that sees and knows your every thought and move, even in your most private moments. The real heart of the matter that Orwell wants you to hold onto is this: you are only as strong as your connection and commitment to your loved ones, your husband or wife, your children, your neighbors, and your countrymen. Once you give those up, you have given yourself up, too.

Every man and woman is weak. We are only strong together and that is not a call to arms or to organize into affinity groups or antifa cells. It is a call to return to the roots that have made every town, every state, every nation strong all throughout human history: the family. Your future depends on it.

A simple chestnut represents the abundance, prosperity, longevity, fertility and hard work’s payoff that all people used to work to create and celebrate together. May it represent the continuation of those energies within humanity’s shared future, so that we may all stand on strong roots, uncorruptible and without end.

Amen.

Thank you for a different take on 1984.

Extraordinary

Hearing you read the poem was so great. Thank you. Great podcast.